"These amazing and accomplished thinkers will be engaging in a discussion about the impressive visual presentation and critical investigations present Amber’s current exhibition on view at our gallery: soveREIGNty: Acts, Forms, & Measures of Protest & Resistance."

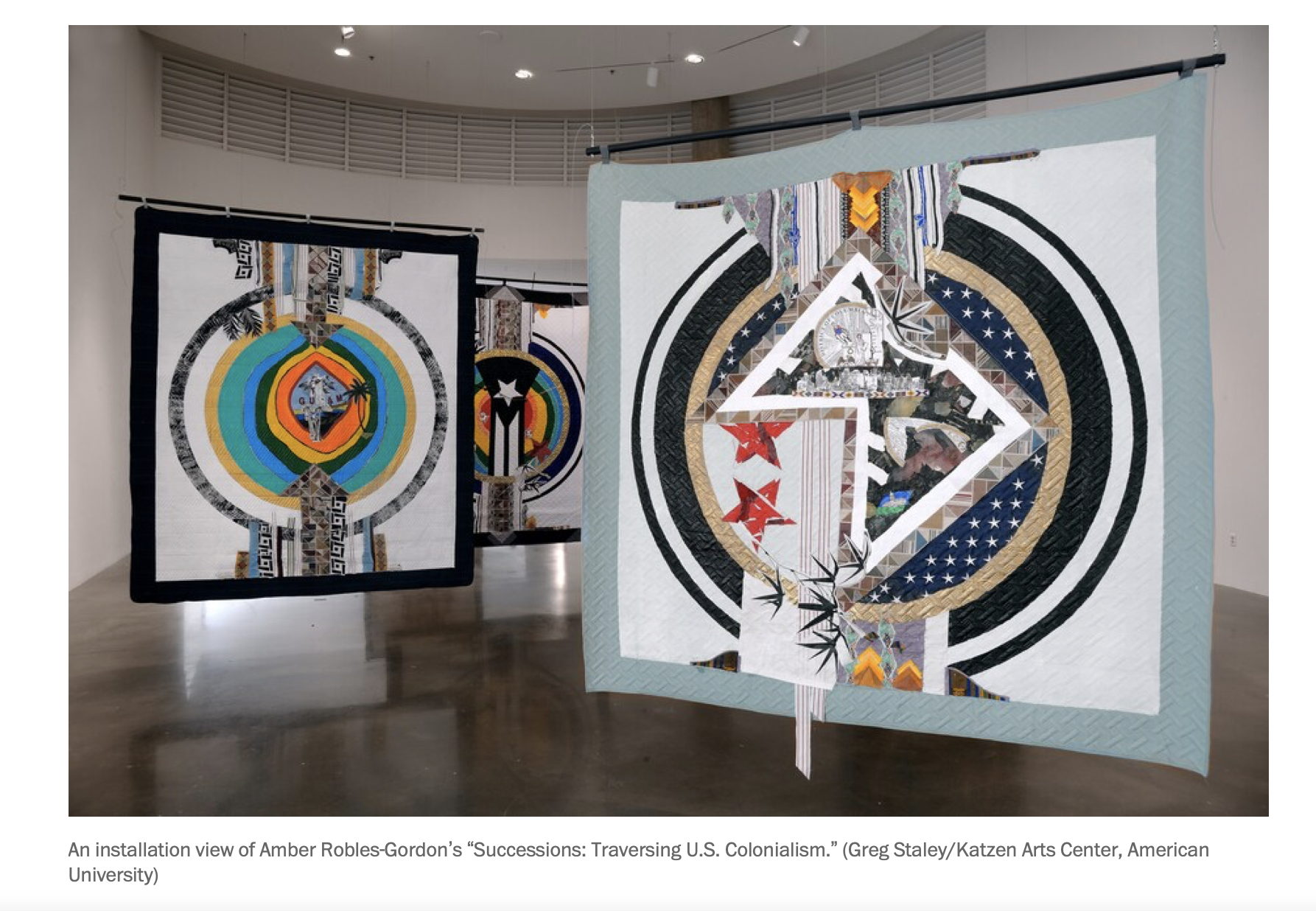

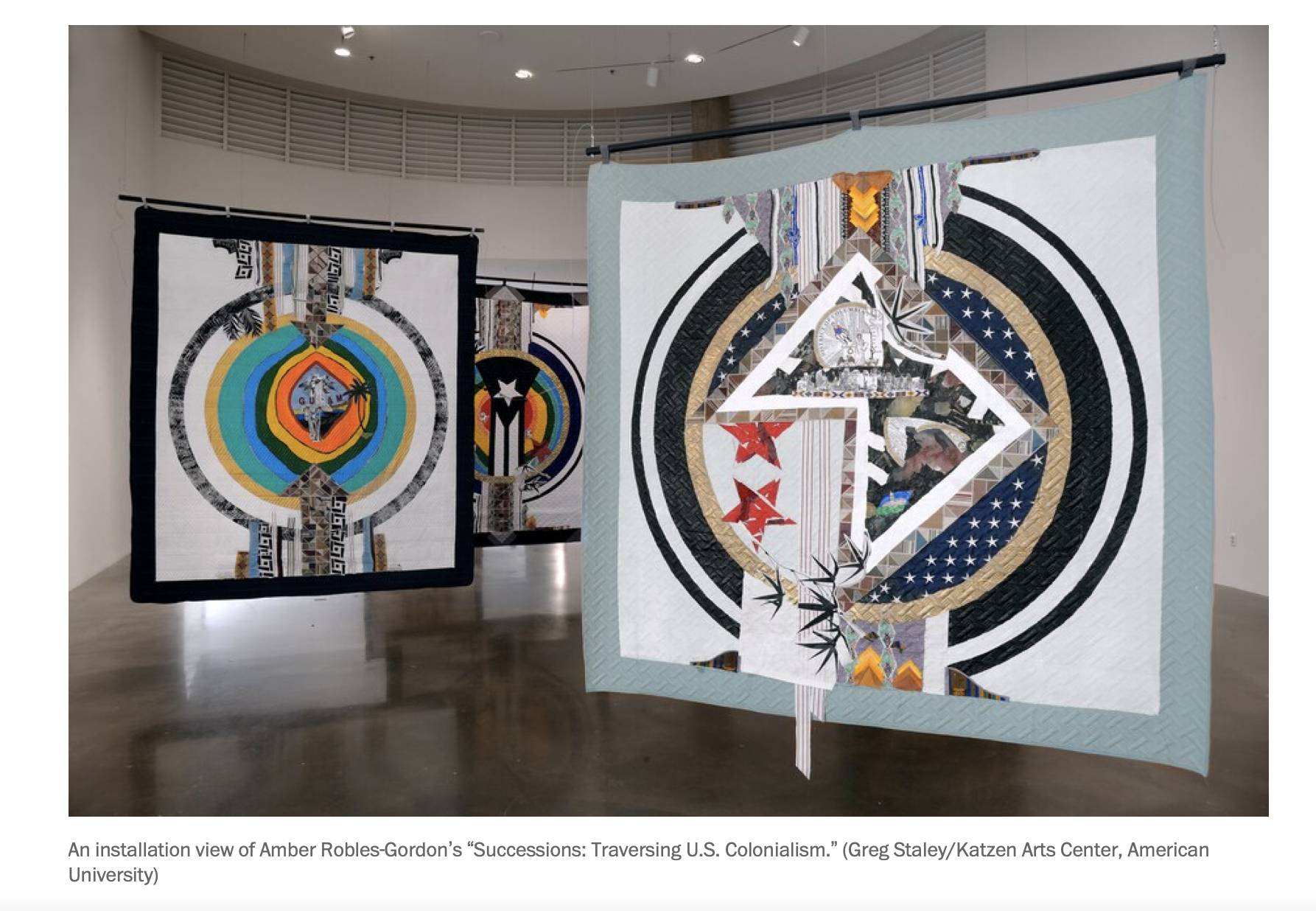

Washington, DC — Seven “flags” hang in Amber Robles-Gordon’s show at the American University Museum: one for each of the five unincorporated United States territories in the Caribbean, one for the District of Columbia, and one to signify the artist’s place in between those locales.

People, food, and horticulture are among the things that move. Amber Robles-Gordon’s use of the Ficus Elastica is part of the symbology that reverberates throughout her exhibition, Successions: Traversing US Colonialism, on view at the American University Museum at the Katzen Arts Center in Washington, DC, through December 12, 2021. The Ficus Elastica—colloquially known as the rubber tree—has its roots in South Asia, though it was later nativized in the West Indies through the rubber trade. Dear reader, among your houseplants you are likely to find the genus of the rubber plant.

Residents of D.C. are used to seeing the place as an almost-state, much like Maryland or Wyoming, yet not quite. Amber Robles-Gordon, a longtime Washingtonian who was born in Puerto Rico, has a different take. Her American University Museum show, “Successions: Traversing U.S. Colonialism,” groups D.C. with her birthplace and four other inhabited territories: Guam, the U.S. Virgin Islands, American Samoa and the Northern Mariana Islands. She represents these disenfranchised territories on two-sided quilted banners, one face for “political” and the other for “spiritual.”

In DC, neighborhoods are facing an unprecedented amount of change in appearance, racial makeup, and social policies that runs counter to the once-prevalent idea of DC being “Chocolate City.” However, there are ways to balance change with paying respects to DC’s living history. The Nicholson Project, an artist residency that recently opened in Ward 7, hopes to demonstrate this change effectively with the inaugural resident artist Amber Robles-Gordon, who lives only eight minutes from the building. For me, it feels like a house turned into a relic, with its period-accurate rehab details; however, the Nicholson Project owners do not focus on the actual former owners, but highlight contemporary artists of color instead.

The mission of the DC Department of Government Services (DGS), according to the agency’s website, is “to build, maintain and sustain the District of Columbia’s real estate portfolio, which includes more than 191 million square feet of state-of-the-art facilities in Washington, DC.” The website says further, “This work allows the agency to foster economic viability, environmental stewardship and equity across all eight wards.”

DC residents may not know that the agency spends approximately one percent of its building budget on public art. Murals, sculptures and other public art seen at DC-owned properties such as libraries, schools and parks derive funding from this source.

Even the title of Amber Robles-Gordon’s Tinney Contemporary exhibition — SoveREIGNty: Acts, Forms, and Measures of Protest and Resistance — expresses an activist message. And it’s emblematic of a display of large-scale, mixed-media quilts brimming with signals and symbolism interrogating U.S. policy toward — and governance of — its populated territories and the District of Columbia.