Amber Robles-Gordon’s Geographies of Care

At the Katzen Arts Center, Robles-Gordon's exhibition conveys a first-person account of the intimacies of movement

December 8, 2021

Words: Sarah Stefana Smith

People, food, and horticulture are among the things that move. Amber Robles-Gordon’s use of the Ficus Elastica is part of the symbology that reverberates throughout her exhibition, Successions: Traversing US Colonialism, on view at the American University Museum at the Katzen Arts Center in Washington, DC, through December 12, 2021. The Ficus Elastica—colloquially known as the rubber tree—has its roots in South Asia, though it was later nativized in the West Indies through the rubber trade. Dear reader, among your houseplants you are likely to find the genus of the rubber plant.

The ficus form appears in Robles-Gordon’s collage series Place of Breath and Birth and the six quilts that comprise Successions, the second body of work and the exhibition’s namesake. “Elemental: Tierra, Aire, Agua, Fuego” (2020), a mixed-media collage from Place of Breath and Birth, uses the ficus to gesture toward culture, genealogy, and place. Here the ficus form spreads from a pregnant middle point, growing outward in four directions, above and below, left and right. Bands of yellow, light blue, teal, and iridescent black paint and paper mimic movement. Most striking is the middle space: the central band of color and ink brings to mind a sonic wave, an echo of the artist’s interest in spirit and culture, the divine feminine, and place—her place, the titular place of breath and birth within the Afro/Latinx diaspora.

Through lines that curve and increase in thickness, “Elemental” vibrates off the wall, exploding the collaged territories’ discrete demarcations through gestures of emergence and slippage. It is here that Robles-Gordon’s practice of collage and assemblage evokes Black life as it exceeds the boundaries of the nation-state and of the medium.

Robles-Gordon made Place of Breath and Birth during a self-defined art residency and while living and traveling between San Juan, Puerto Rico, and Washington, DC—a period of time disrupted by Hurricane Isaias and the COVID-19 pandemic. In Successions, we encounter her motifs and movements within a broader practice. Robles-Gordon is a DC-based artist whose family lineage is in the Black diaspora with ties to Puerto Rico and the greater Caribbean. These diaspora ties are reflected in creative and cultural traditions she draws from, including the Washington Color School, Alma Thomas, the Gee’s Bend Quilters of Alabama, and botanical elements within Afro-Latinx religions.

The artist’s exhibition conveys a first-person account of the intimacies of movement—and the past’s effect on the present through empire, colonialism, and transatlantic slavery, of which territory is a major mechanism. Place of Breath and Birth and Successions both invite us to think about the territory and what Caribbeanist scholar Sylvia Wynter has named “mistaking the map.” In the article “On How We Mistook the Map for the Territory,” Wynter describes the mistaken map as a series of factors of difference in academic discipline, and in social contexts, that conscribe a particular meaning of “human” to the current social order. The consequences of this mistaken map are that what it means to be “human” is conscripted through logics of belonging that reflect a worldview that excludes, proliferates violence, and is upheld by the state. In Robles-Gordon’s hands, mistaking the map means we must contend with the entanglements of colonialism and empire—and the spiritual resonance of it all—in the wake of violence.

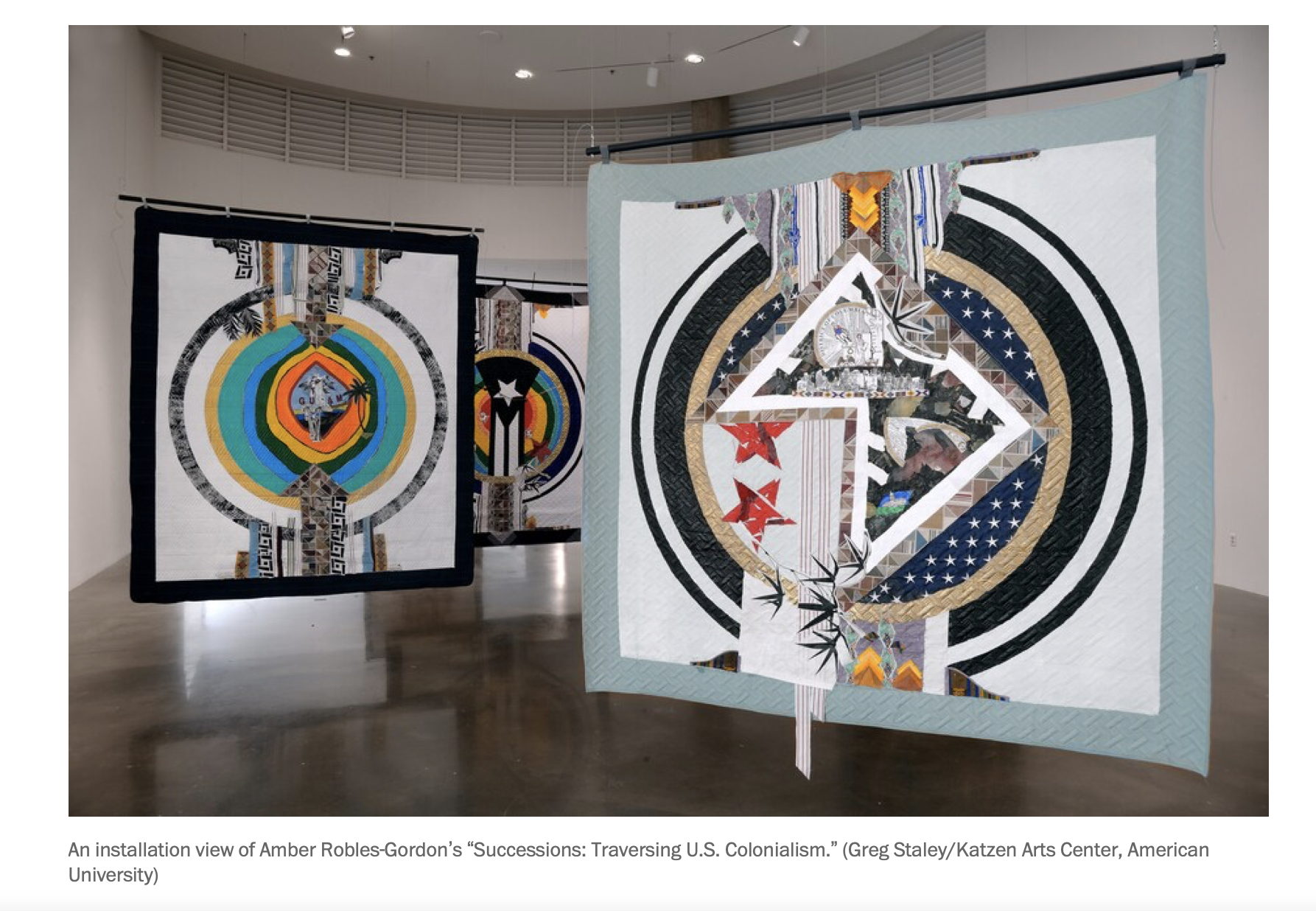

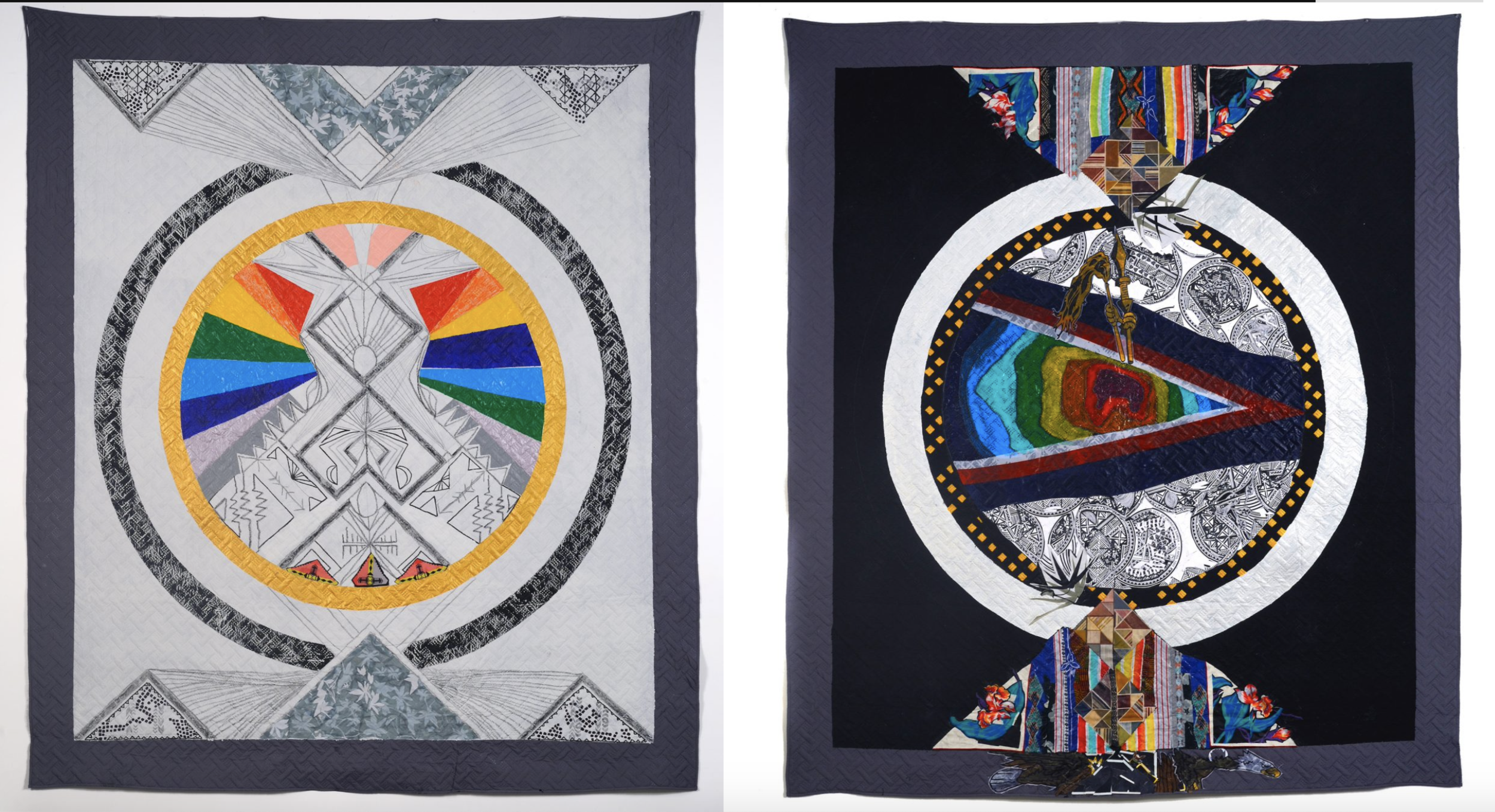

Place of Breath and Birth bears the mark of one of the United States empire’s territories, Puerto Rico, referencing the artist’s personal relationship to its people, land, and culture. Successions take a more hemispheric approach. This series comprises double-sided quilts standing in for five territories of the U.S. empire—Puerto Rico, Guam, U.S. Virgin Islands, American Samoa, Northern Mariana Islands—and the District of Columbia, a federal district. While one side of the quilts represents the territories through symbols like flags, eagles, and other emblems of the state, the reverse intones a spiritual element, the cultural heart of these geopolitical spaces. This second orientation to the quilts, which are suspended from the gallery ceiling like flags in a federal building’s rotunda, upends a logic of conquest by inviting viewers to encounter them through another path.

The sixth quilt, the first completed in the series, titled “When All is Well (Front)” stands out with its color palette of red, green, and sunburst orange against a black background. With paint and fabric stitched together, the quilt holds symbology of flora, fauna, and deconstructed text that contrasts with a pattern of white geometric lines and marks. From the quilt’s outer reaches comes a cascading element of green and brown lines and curves and triangular patchwork, and a pink-and-yellow bloom disrupts the earthen tones. A circular area with symmetrical marks, resembling eyes, is composed alongside what might be a talisman hanging in sunburst orange. “When All is Well/The Hawk (Back)” continues motifs of flora and fauna, alongside a black background where line and mark bring together symbols reflecting latent and less obvious cultural and social inflections of being.

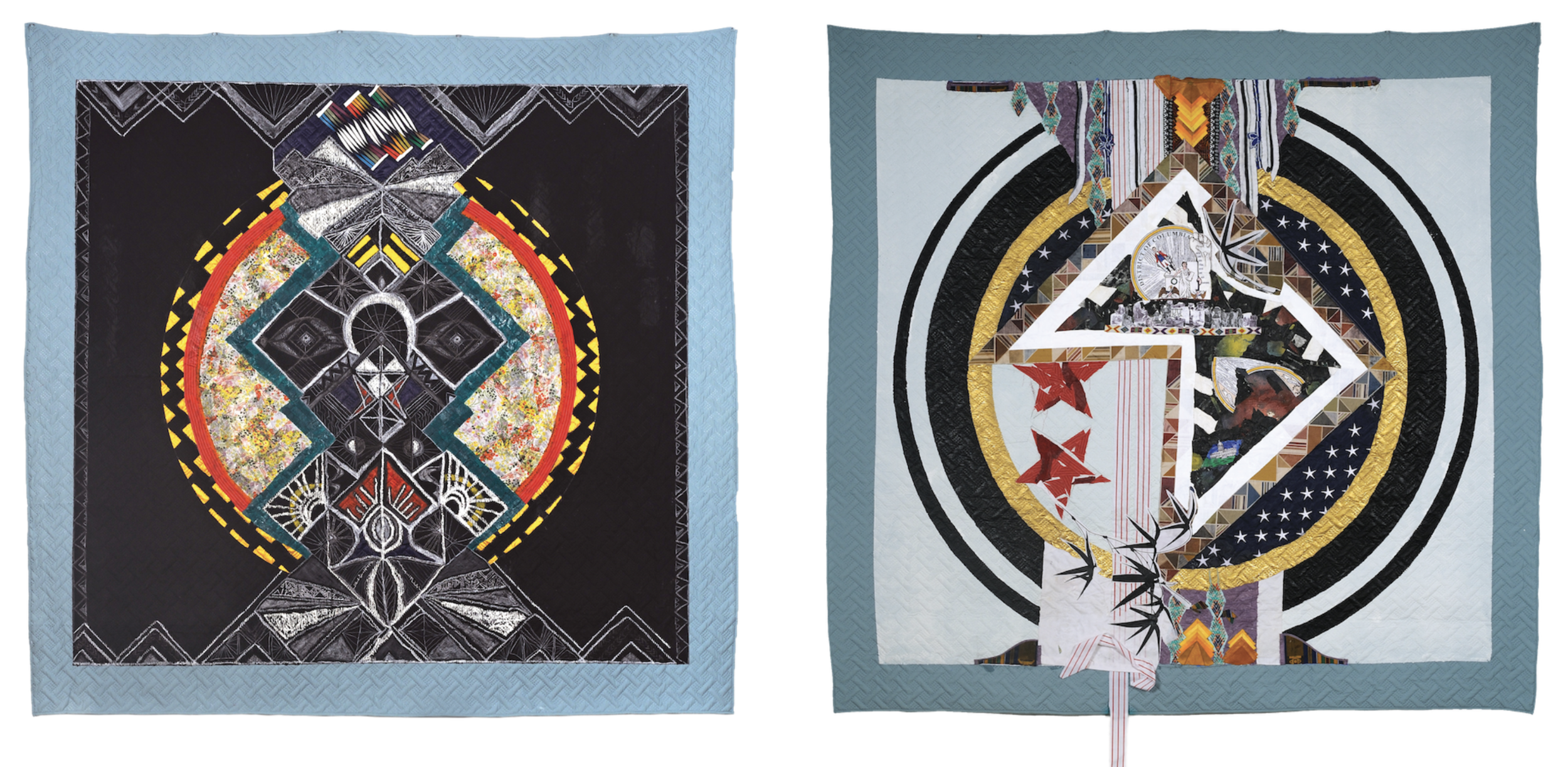

How necessary that the District of Columbia—the political seat of the US empire and a geopolitical place vying for its own statehood—would factor into Successions. “DC Political, Welcome to the District of Colonialism” and its reverse, “DC Spiritual, Native American,” evoke the duplicity of empire and subjugation, culture and acknowledgment.

On “DC Political,” Robles-Gordon deconstructs the seal and the flag that marks the territory, pulling at the seams of the spangled banner’s stars and stripes and the district’s spatial dimensions. An insignia where Lady Justice hangs a wreath at the George Washington monument sits off-kilter and atop a depiction of indigenous presence—in a place where the Piscataway, Pamunkey, Nentego (Nanichoke), Mattaponi, Chickahominy, Monacan, and Powhatan cultures thrived. These depictions are housed in the outlined topography of DC as a landscape. The other view, “Native American,” produces a hieroglyphic of symbol, line, and color that suggest the heart/soul of a presence that thrived, championed expansive visions of existence, and yet is constantly erased. This view acts as a portal, building a world that can be imagined outside of subjugation and conquest, one that can imagine the multivocal breadth of care as a collective practice against such dehumanization and erasure.

Empire makes inroads through racialized gender. The fact that textile art has always been gendered (due to its connotations with craft, domestic space, the labor of women, and the feminine) is well-trodden territory. National imaginaries and territory, meanwhile, are constructions of masculinist notions of conquest and control; the infantilization of the native/colonial subject often stands in as a proxy for gendered labor. Taking bits and pieces of colored fabric and material and assembling them into an amalgamated whole, Robles-Gordon’s technique harkens back to gendered labor and care.

Take, for example, “The eternal altar for the women forsaken and souls relinquished. Yet the choice must always remain hers.” (2020), from Place of Breath and Birth. This work draws on the histories of experimental birth control trials and forced sterilization of poor Puerto Rican women between the 1930s and 1970s, and the notion of bodily autonomy alongside the process of reclamation. Forced sterilization, a dehumanizing form of state systematic violence, was exercised to curtail poverty and unemployment, and it intersects with early forms of gynecological testing on enslaved people.

In Robles-Gordon’s collage, blood red brings into focus the embodied ways that racialized and gendered labor produce the violence of empire. We might also see connections to women and queer rebellion, in the Black Lives Matter movement, and the retooling of naming Blackness on census data in Puerto Rico through the efforts of groups such as Colectivo Ilé and Revista Étnica. As a navigation of the roots and routes of Puerto Rico’s colonial past and present, the mixed-media collage invites viewers not simply to witness horror, but to build and acknowledge care as a revolutionary practice that transforms how people interact with one another and how they interact with place.

In her book In the Wake, Christina Sharpe writes of care work as a labor in which Black diaspora people insist on life-giving practices alongside the singularity of slavery, to hold space for Black life. Care is woven through Robles-Gordon’s work: These mixed-media collages are potent worlds where touch is a critical factor in their making. The detail in which black bits and pieces give way to the constellations of color and line, fragmented yet collective, ruptures a too-easy analysis of collage as a process of making that dissects and creates categories of materials like an index. Quilts are sensory, touch-based work; they invite exploration of the haptic and of intimacies with space.

I return to the presence of the Ficus Elastica as a symbol throughout Place of Breath and Birth and Successions. While the formal qualities of the ficus are more readily present in Place of Breath, it is a motif of importance in Robles-Gordon’s work. It becomes a way to get behind and underneath the spatial politics of the territory, and toward a politics of care, where people on the land forge their own experiences, make culture, and fortify community in spite of empire.

Words: Sarah Stefana Smith

Images courtesy of American University/Katzen Arts Center. Art images courtesy of the artist. Exhibition installation photos by Greg Staley